A proposed centre of excellence (SFF), Quark-Lab will build a bridge between the collider physics and gravitational wave astronomy communities based on fundamental theory.

Physicists in the 20th century have revealed the microscopic structure of matter. They discovered that atoms are made of electrons surrounding a nucleus made of protons and neutrons. In the 21st century physicists set out to uncover the remaining mysteries of matter at even smaller scales, peering into the interior of protons and neutrons, which are made up of yet another type of elementary particle, so called quarks.

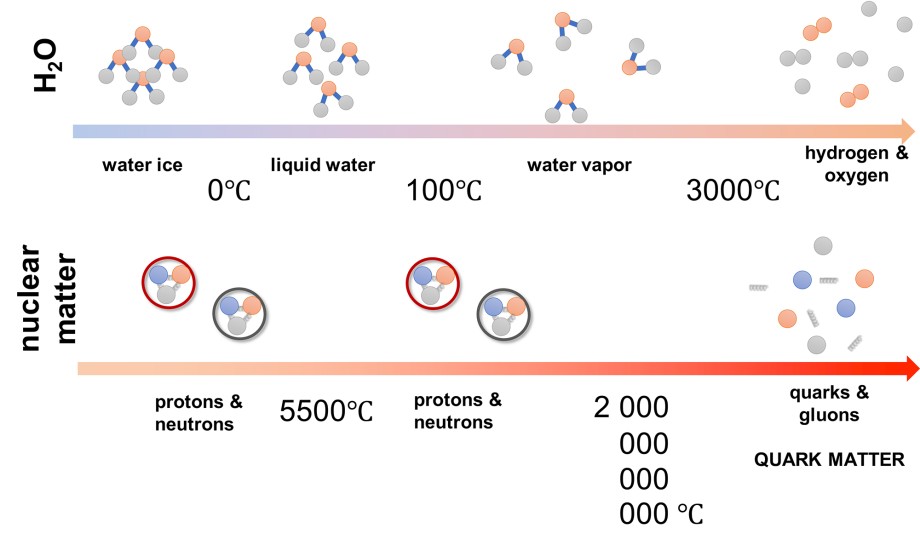

It has always been of interest for physicists but also for inventors to understand how the properties of matter change, as we increase or lower the temperature of a material (think of a steam engine). For water we are all familiar with its three major phases, ice, liquid and vapor, which transition from one to another at specific temperatures. If you really want to go extreme, you can heat water up to around 3000℃ and observe how the molecular bonds are ripped apart and water vapor dissolves into a gas of hydrogen and oxygen.

Credit: Alexander Rothkopf, UiS

At the proposed Quark-Lab centre of excellence, physicists from UiS take aim at a similar process that happens to the protons and neutrons of the nucleus itself. Heating protons and neutrons to the temperature of the sun (5500℃) leaves them completely unharmed. They are much more robustly bound than water molecules. You need to go to incredible temperatures of 1012 ℃ (yes you read correctly: 12 zeros) to see them dissolve into their microscopic parts. It is at these temperatures that quark matter comes into being and its properties can be studied.

Such extreme temperatures were present shortly after the Big Bang and by learning about how matter behaves under such circumstances helps us understand the origin and early moments of our universe.

But where can one study quark matter today?

The members of Quark-Lab are experts in modelling and experimentally investigating quark matter. One team will investigate quark matter that is created in collisions of nuclei at the international CERN accelerator laboratory in Switzerland, of which Norway is a founding member. Team members will develop novel computer simulations and data analysis tools to extract the properties of quark matter from these collider experiments with a precision unmatched to date.

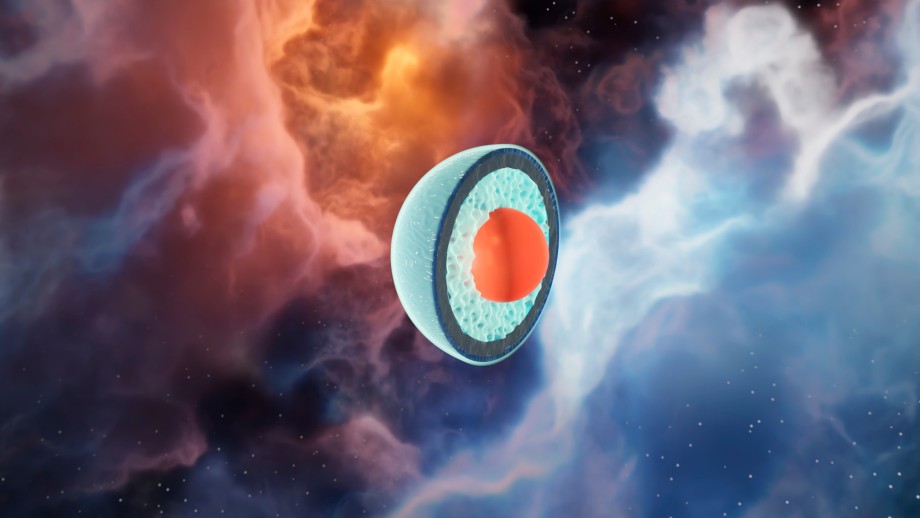

One of the other teams takes a look at some of the most massive astronomical objects that exist in the universe today: neutron stars. Using the experimental technique of gravitational wave astronomy, which in 2017 was celebrated with the Nobel prize, they can observe when two such neutron stars collide. In one scenario, these incredibly massive objects collide, and friction creates temperatures similar to those close to the Big Bang, possibly creating quark matter in the collision centre. Such a collision in turn leads to measurable signals that our team members set out to analyze and model.

What distinguishes Quark-Lab from other research centres is its strength in theoretical physics. The third team of Quark-Lab consists of world-leading experts in computational methods that allow us to translate the fundamental laws of physics into testable predictions. These capabilities allow Quark-Lab to build a bridge between the collider physics and gravitational wave astronomy communities based on fundamental theory.

The proposed centre is associated with the Department of Mathematics and Physics at the Faculty of Science and Technology, UiS. The research team, the majority of which is located at UiS, welcomes collaborators from the University of Bergen, Lund University and the Instituto de Ciencias de l'Espascio in Barcelona and is led by Alexander Rothkopf and Aleksi Kurkela here at UiS.

The Quark-Lab has applied for Norwegian Centres of Excellence (Sentre for fremragende forskning – SFF).