The most common thing about countries that are 'successful' in PISA, is a higher level of gender equality in the population.

"Yes, it was surprising to me! Initially, I thought that income equality, the degree of even distribution of income in the population, was going to be the most consistent factor. But it turned out instead to be gender equality," says Janine Campbell, a researcher at the Learning Environment Centre, University of Stavanger, about her findings.

International background, international research

Born and raised in New Zealand, resident in Chile from 2000 to 2020, and now living in Norway, Campbell’s personal story fits very well with this field of study – research on international relations, cooperation, and policy, particularly in the education sector.

In Campbell's article, she examined the educational policy and socioeconomic conditions behind the results in 49 of the 72 countries who participated in the 2015 PISA survey (OECD members and partners).

Good school results in equal countries

Through comparative analyses of both a qualitative and quantitative nature, Campbell examined how PISA results and school policy in the 49 countries were associated with socioeconomic and cultural factors.

Among these factors, the degree of economic equality, development, and individualism were key factors, as well as gender equality (as measured by the UNDP Gender Inequality Index).

But the latter was most consistently associated with educational outcomes, both in a positive and negative sense, in this PISA study.

“Among the countries that scored higher than the OECD average on PISA results, Poland was the only country that did not score higher than the OECD average on gender equality – and they were close to being included in the latter group. At the other end of the scale, the countries that performed poorly were even more consistent: All the countries that scored below the mean in PISA 2015 were also below the OECD average on gender equality,” Campbell points out.

She emphasises that the other factors mentioned are also important for creating good societal conditions for good schools, but that the findings show how central gender equality is to creating development, both within the school and in society.

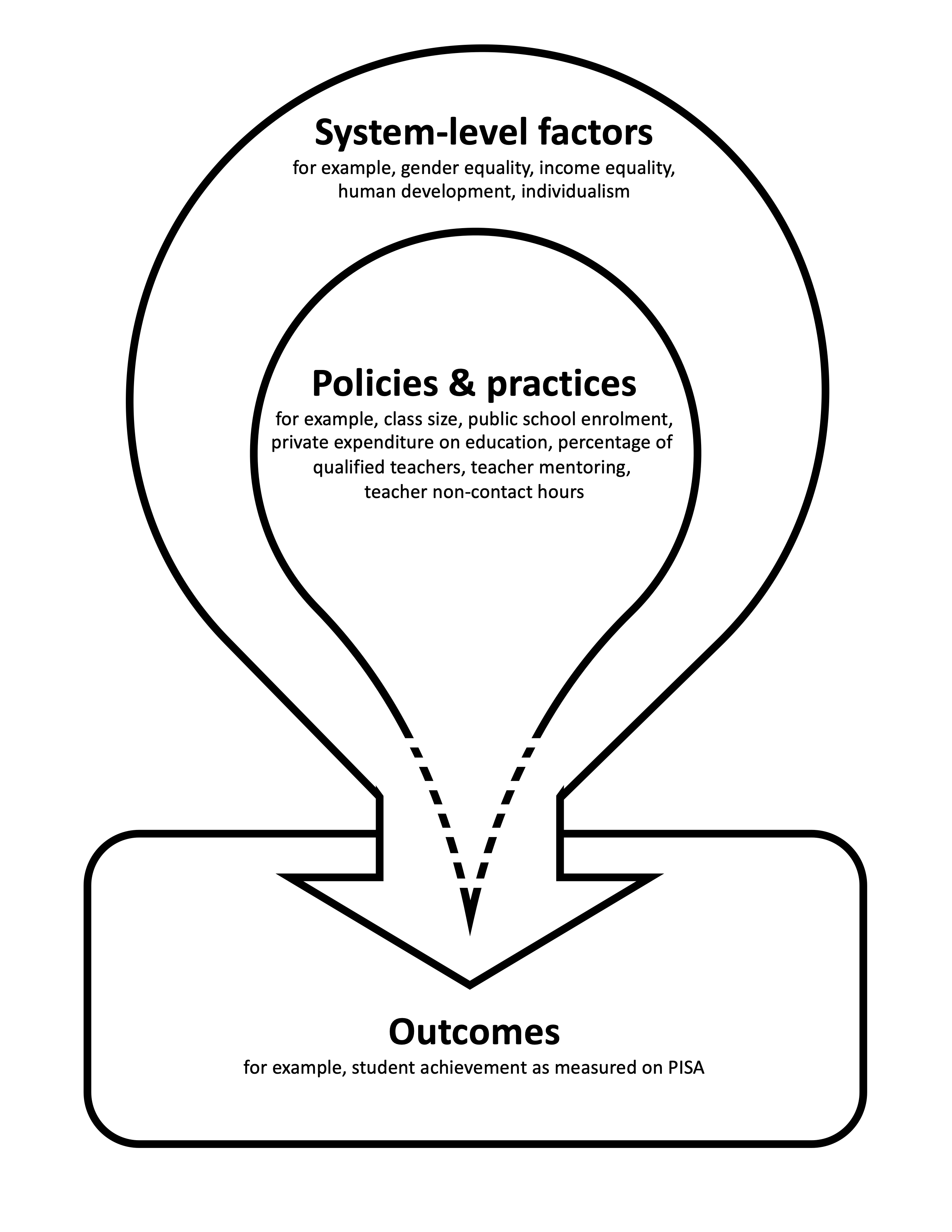

(Image: Campbell, 2021)

“One may be more likely to 'blame' factors such as lack of income equality than gender equality when living in a poorer performing country. I remember myself being of such an opinion, after my experience in Chile over 20 years. And do not get me wrong, of course the other factors are important, and of course they are also connected, often in complex ways. Nevertheless, the findings of this study show that we must recognise the importance of gender equality in all aspects of society when it comes to creating schools that benefit everyone," says the researcher.

Some countries surprise positively

The fact that countries such as Norway and Sweden are doing well in the PISA survey is hardly surprising in this context, as they also score very highly on prosperity, economic development, and gender equality.

Possibly more surprising for researchers, is to see nations such as Estonia and Portugal with such positive indicators.

“These countries are not particularly rich in the OECD context, nor have they traditionally been regarded as particularly equal. But gender equality has improved rapidly in both Portugal and Estonia, and this may be one reason for their good results in the PISA survey. They're interesting countries to keep an eye on," Campbell says.

Despite the fact that these are European countries, the picture is far from marked by an unambiguous "West against the rest" chasm: Japan, South Korea, and Singapore are non-Western countries that are high in both the PISA scores and on the list of countries that score above the OECD average in gender equality.

It should also be noted that there are countries that have higher levels of gender equality but are not among the best in the PISA survey, such as Austria, Greece, and Italy.

The study therefore does not prove that gender equality alone leads to higher PISA rates.

“We must also keep in mind that the differences in this field are enormous, both within the OECD and between these 49 countries and the rest of the world. For example, even the poorest of the OECD members are very rich compared to the least developed countries in the world. Large parts of the world, including the vast majority of Sub-Saharan Africa, do not have the economic opportunities to participate in any PISA survey at all. The gaps around the world are so large that they are almost unfathomable,” Campbell explains.

One may be more likely to 'blame' factors such as lack of income equality than gender equality when living in a poorer performing country.

Implications for education policy

In addition to showing how gender equality in society is associated with educational results, the study reveals that education policy initiative may have different results in countries with different social structures - particularly in countries with different degrees of gender equality.

For example, there is no relationship between small increases in class size and PISA results in countries with a high degree of gender equality (where class sizes are usually small to medium to begin with).

But, in countries with a low degree of gender equality, there is a significant and strong correlation between an increase in class sizes and pupils' results in the PISA assessment, in a negative direction.

“As a society, we must therefore pay more attention to these system-level factors – development, degree of economic equality, gender equality, and so on – and the moderating effect they have on education policy, school practices, and educational outcomes. One should avoid a 'copy and paste' strategy – in which one country, oblivious to context, adopts policies or initiatives that have been successful in another country where the system level factors may be completely different.”

(Image: Campbell, 2021)

"Do you have examples of such a strategy?"

“In Chile (and many other countries), we often talked about 'looking to Finland', or to Europe or the USA, based on a kind of logic that if they can, we can! But such a comparison or ambition is meaningless – because the social, economic, and cultural conditions are so different among these countries. The gap is too large for the desired changes to be possible to implement, and if implemented in such different contexts, are unlikely to have the desired result," Campbell says.

"Who should Chile look to, then?"

"Maybe Portugal. This country could be considered and aspirational peer, given the similarities in population, prosperity, and income equality between the two countries."

Progress over time matters

In another study, researchers examined the longitudinal relationship (2006-2018) between PISA results, gender equality, and human development. Here too, positive change in societal gender equality was found to be the most consistent predictor of positive change in PISA scores, adding to the growing body of work showing that improving gender equality improves social outcomes for all.

Initiatives in education and schooling should therefore start with a broader focus.

"Instead of focusing on imitating successful school systems to improve education - with the underlying idea that an improved school should improve society - we need to work more broadly to develop and improve the whole community, and include the school in this work. It does little to build schools if there are current practices or structures that have children working outside of school, girls kept at home for domestic duties, an absence of female leaders, or inequalities resulting in real opportunities only for the wealthy," Campbell says.

She concludes:

"Based on this research, my message is that raising the status of girls and women in society - in areas such as health, income, property rights, and political influence - may be a quicker way to improve schools and educational outcomes, than to go the opposite way and focus specifically on education in order to create gender equality in turn. In other words, it is probably more effective to create gender equality on a broad front first, than to believe that more equal schooling will lead to equality elsewhere in a society. History is showing us that this latter approach is just too slow for the change that this world needs now.”

References:

Campbell. The Moderating Effect of Gender Equality and Other Factors on PISA and Education Policy, Educational Sciences, vol. 11, 2021. DOI: 10.3390/educsci11010010

Campbell, McIntyre and Kucirkova. Gender Equality, Human Development, and PISA Results over Time, Social Sciences, vol. 10, 2021. DOI: 10.3390/socsci10120480

Text: Leif Tore Sædberg

Personer omtalt i denne saken

Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment and Behavioral Research in Education